Three operas portray the trancelike state of love, from a world-premiere production exploring the intimate bond between John Singer Sargent and his male studio model to Debussy’s classic tragedy and Purcell’s intoxicating adaptation of Shakespeare.

By Heidi Waleson

July 22, 2024 at 5:27 pm ET

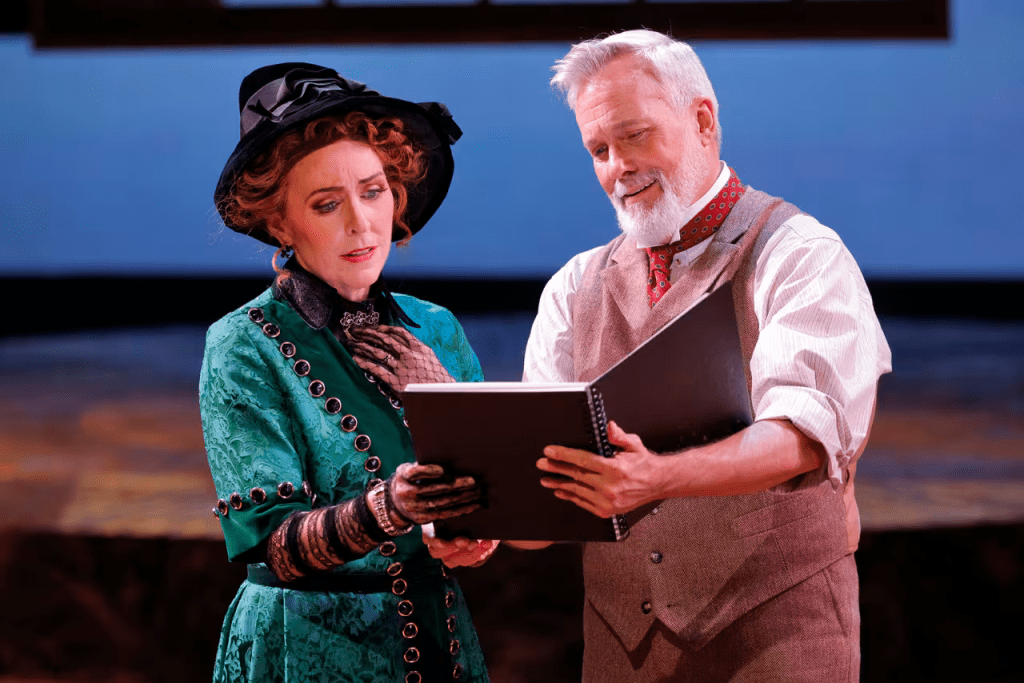

Justin Austin and William Burden in ‘American Apollo.’

PHOTO: CORY WEAVER

Indianola, Iowa

“American Apollo” by Damien Geter and Lila Palmer, which had its world premiere at Des Moines Metro Opera earlier this month, touchingly imagines the artistic and erotic relationship between two real people. In 1916, the celebrated painter John Singer Sargent met Thomas McKeller, a young black man working as a bellhop and elevator operator at a Boston hotel. For the next decade, until the artist’s death in 1925, McKeller was Sargent’s model for his murals at the Museum of Fine Arts, his body transformed into those of gods and muses, both male and female. Sargent’s sketches of McKeller prompted a 2020 exhibition at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum accompanied by scholarly exploration of their story.

For DMMO, Mr. Geter and Ms. Palmer expanded their 20-minute piece commissioned by Washington National Opera’s American Opera Initiative into a full evening. There are extraneous characters, occasional talkiness, and some plot points that feel artificial, but when the creators delve into the emotional intimacy and fervor of the relationship, the opera blossoms. Ms. Palmer’s libretto deals forthrightly with the complexities of its central theme—the power imbalance between a prominent white man and a working-class black one, exemplified by the fact that Sargent’s MFA paintings of McKeller’s body show him as white, with classical heads instead of his own. Was Sargent simply using McKeller, or did he truly see and care for him?

The opera’s most affecting moments revolve around the melding of artistic inspiration and growing love in Sargent’s studio. They include Sargent’s first caressing aria (“Magnificent. Extraordinary.”), about how McKeller’s body and modeling skill have moved him, and later, a tender duet of mutual seduction as Sargent tells the stories of the gods and McKeller finds them in his poses. Mr. Geter’s lyrical music is at its strongest here; he also integrates Reynaldo Hahn’s perfumed chanson “À Chloris,” which the two men sing together, as a love motif. Two scenes of reconciliation in Act 2 are similarly charged with tenderness. When the opera moves outside their dyad and into the rest of the world, its magic dissipates, and the music feels routine.

Mary Dunleavy and Mr. Burden

PHOTO: CORY WEAVER

As McKeller, baritone Justin Austin combined yearning, intelligence and prickliness; his anguished aria “This is my body,” questioning Sargent’s motives, was a dramatic high point. As Sargent, tenor William Burden found the aging artist’s spark and sincerity. As Isabella Stewart Gardner, Sargent’s friend and patron, who keeps the duo going whenever it threatens to fall apart, Mary Dunleavy was effervescent, although her high coloratura had a strident edge. Of the numerous cameo roles, the two largest were ably discharged by Alex McKissick as Nicola d’Inverno, Sargent’s former model and lover, and Tesia Kwarteng as Ida Mae McDonald, McKeller’s friend and confidante. David Neely was the sensitive conductor, skillfully handling the transparent orchestrations and evocative interludes.

Director Shaun Patrick Tubbs and scenic designer Steven C. Kemp made good use of the Blank Performing Arts Center’s eccentric stage (it has a hole in the middle through which the orchestra can be glimpsed). Sargent’s studio occupied the front area; most of the other scenes took place upstage. Reproductions of Sargent’s paintings established the studio scenes and provided a dramatic final reveal: After the artist’s death, McKeller uncovers the powerful nude portrait of the model as himself (it is now in the MFA), and his doubts vanish.

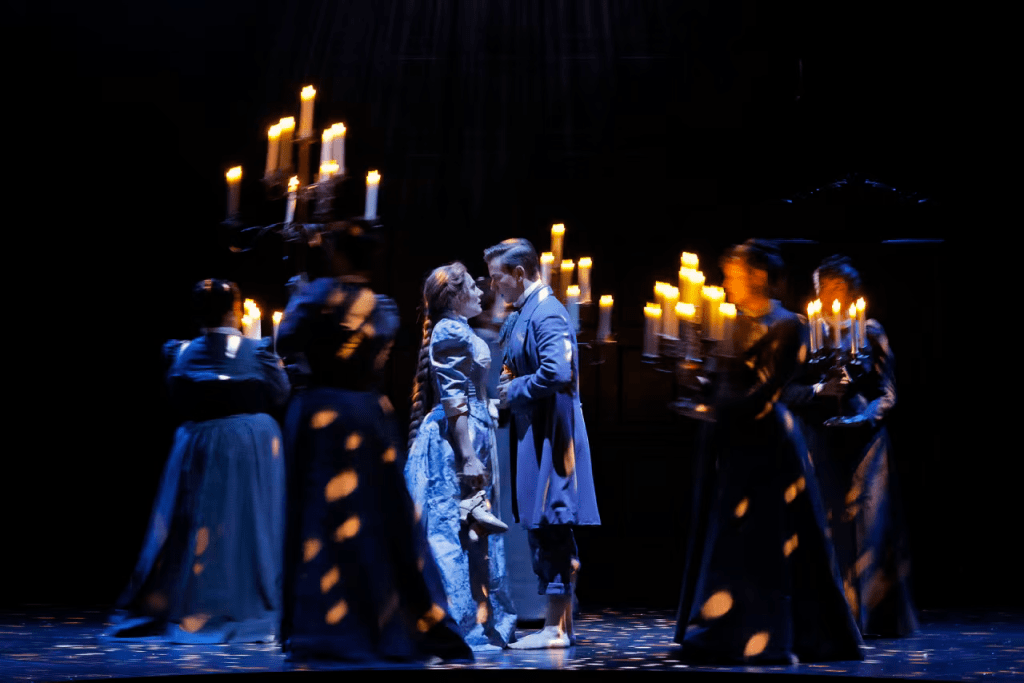

Sydney Mancasola and Edward Nelson in ‘Pelléas & Mélisande.’

PHOTO: CORY WEAVER

Debussy’s “Pelléas et Mélisande” was performed with sinewy directness rather than lush impressionism—the smallish orchestra under Derrick Inouye sounded undernourished for this score and Chas Rader-Shieber’s direction avoided ambiguity. The clear motivations were bracing at first, thanks to the three excellent principal singers. The violent temperament of Golaud (Brandon Cedel) was established from the beginning, the mutual erotic attraction of Pelléas (Edward Nelson) and Mélisande (Sydney Mancasola) was explicit and adult, and all three understood the consequences of their actions. But Mr. Rader-Shieber’s additions at the end—Golaud kills himself and the old king Arkel, eloquently sung by Matt Boehler, also dies, leaving the boy Yniold (Benjamin Bjorklund) to circle the stage hole with Mélisande’s baby in his arms—produced a Shakespearean massacre at odds with the opera’s mood of perpetual gloom.

Andrew Boyce’s somber, claustrophobic scenic design used a coffered wood backdrop and an armoire that became a kind of magical door to other realms—its bottom drawer was pulled out to become the fountain where Mélisande loses Golaud’s ring. Lighting designer Connie Yun kept the shadows long; Jacob A. Climer’s early 20th-century costumes hit their mark, especially when Mélisande, arriving at the castle, is trussed into a full corset, bodice and skirt. Once her romance with Pélleas is under way, she wears filmy nightwear; as she dies in the now snow-filled armoire, she has regressed to the traumatized state in which Golaud first found her.

Katonah, N.Y.

Purcell’s “The Fairy Queen” (1692), presented on Saturday at Caramoor by Les Arts Florissants, was a delightful updating of this series of masques intended as interpolations in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Director and choreographer Mourad Merzouki deftly integrated eight singers and six hip-hop dancers into a lively, playful company portraying a magical night of abandon—drunkenness, sleep, love (happy and sad), nature and the seasons, marriage, and a return to the real world.

Cast members wore black trouser suits (by Claire Schirck), stripping off their jackets midway through to reveal colored shirts, and the athletic movement idiom—complete with breakdance headstands—went surprisingly well with the centuries-old music. When mezzo Georgia Burashko invoked spirits, dancers rose up from the floor, spinning into turns with a single motion, and everyone danced and sang the final chaconne and chorus.

The musical high point was mezzo Juliette Mey’s poignant rendition of “O let me weep,” with violinist Augusta McKay Lodge following her around and echoing her sighs. Even the conductor, William Christie, was part of the action: Standing between the orchestra, positioned upstage, and the cast, he gave some cues but mostly faced the audience and mouthed the words. However, the excellent players, complete with a sensitive continuo section, clearly knew exactly what they were doing.

Ms. Waleson writes about opera for the Journal and is the author of “Mad Scenes and Exit Arias: The Death of the New York City Opera and the Future of Opera in America” (Metropolitan).

Appeared in the July 23, 2024, print edition as ‘Stories of Art and Attraction’.

Dear Andy,

I will be at Glimmerglass August 15 and 16. Will you be there then too?

Neal

>

LikeLike

Andy, thanks so much for sending these. I’ll enjoy reading them. 🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person