These reviews first appeared in The Quarterly of the Lute Society of America in significantly altered form.

The modern guitar dominates the commercial music we hear in the west. Since the time of Elvis Presley and the Beatles, bands made up of fretted instruments and percussion have become the convention in popular music. The tradition of the players of guitar being the stars of non-religious art music is a long one, and includes not only Spain, but France, Italy and England as well. The idea of the guitarist improvisor/composer/performer is also not a new one.

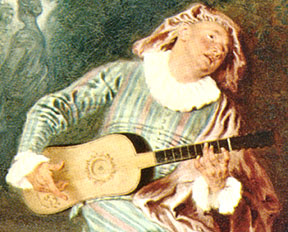

The baroque guitar is one of the several variations on historical fretted instruments, of which the most well know is probably the lute. The baroque guitar was in its time perhaps most widely heard accompanying comic arias in operas of the baroque. In Latin American music of the period, is can similarly be part of a jubilant rhythm section playing in the rasqueado (strummed) style. There is a substantial solo repertoire of secular music, some of which is now played by modern guitarists. But the instrument remains somewhat obscure in the modern world, especially since it is difficult to perform as a soloist in public under contemporary concert circumstances due to its lack of capacity to project and the low volume of sound it produces (particularly when played in the punteado (or plucked) style. But digital recordings are a godsend for this music, because of the immediacy made possible by the microphone and the ability to crank up the volume, if one so desires.

It is therefore particularly remarkable, given the relative invisibilty of the instrument in the wider world that so many recordings of the baroque guitar and its music have landed in the “in-box” of the LSA in recent years. Musicians seeking to perform this music must not only become expert in the appropriate style, rhetoric and ornamentation for the genre, but they often must create their own performing editions from manuscripts or period printings. Clearly, playing this music, like most of early music for fretted instruments, is a labor of love – and certainly not a dry scholarly exercise. Several of the performers, playing at a high level of technique and sophistication, are names that were previously unknown to me. What follows is a report on the several disks that have piled up at the LSA featuring the historical guitar.

Sones del Viejo Mundo, Miguel Rincón, 13 Tracks, 62’20, 2019

The glory of the music for baroque guitar is Spanish music from about 1675 to about 1725. Principal composers, familiar to students of historical guitar (but not, generally, to those knowledgeable about Western art music) are, of course, Gaspar Sanz, Francisco Guerau and Santiago de Murcia – all featured on this album by the Madrid-based guitarist Miguel Rincón. Sones des Viejo Mundo is a wonderful introduction to the music of these composers and of this period, comprised of some of their greatest hits – at least among baroque guitar cognoscenti. And, while the title of the disk makes reference to the influences of the New World, the rhythms of which are obvious features of much of this music, influences from Italy and France are also noticeable. This blend of musical ideas is very much what we now regard in the aggregate as Spanish. Also tying this music together, and providing a Latin American flavor is the regular presence of a repeating ostinato base line in many of the pieces played here.

Rincón has studied with the best, including Xavier Diaz-Latorre and Eduardo Egüez, and possesses a straightforward, theatrical, aggressive style. The liner notes don’t tell us anything about the player (which can be found on his website) or his instrument (which cannot). The notes do spend some time discussing the different stringing of the guitar for each of the three different composers (While the same tones are used on each of the courses, the use of lower octave strings on each of the different courses varies with the composer). While this theoretically affects the playing in a companella style, this is one of those issues that music historians and players of fretted instruments like to discuss endlessly, in which no one else is interested, and which are imperceptible to even a sophisticated listener. However, if they make a player happier – then so be it.

The sound on this recording is closely miked; immediate and present, with a great deal of detail able to be heard – for better and for worse in this instance. The playing is strongly rhythmic and highly ornamented – almost virtuosic. The ornaments are attacked. Several of the tracks feature variations (differencias) on classic patterns (xácaras, canarios), which would benefit from more actual differentiation of the playing between them. Some of the faster and more complex ornaments, polyphony and divisions sound smudged.

There is a reason that these dances continue to be played and enjoyed – and Rincón makes a fine case for them. They are not only lively and rhythmically inventive, but also all three of these composers have a melodic gift, which is the rarest of musical capacities. Much of what is recorded for baroque guitar (as well as for the lute) is an attempt to bringing to light previously un-played or unrecorded scores. Great music gets played and recorded often, as here, because it gives great pleasure to both performers and listeners. While it is interesting to hear recently discovered works realized in performance, neglected music has only occasionally been ignored unjustly — but usually not.

Domenico Rainer/Music for Baroque Guitar, Lex Eisenhardt, Brilliant Classics 2018, 53’18, 27 tracks

The genesis of this recording is a newly discovered manuscript in the National Academy of St. Cecelia in Rome. Among the works in this 230-page document are pieces in dance and dance suite forms attributed to a previously unknown composer named Dominico Rainer and composed around 1700. These 27 pieces are performed by Lex Eisenhardt on a Bert Kwakkel copy of a Stradivarius guitar, using gut strings. Eisenhardt is an Amsterdam-based guitarist, and the liner notes state that his was the first to record the music of Sor on a period instrument in 1981. The guitar is tuned in “a” and “b,” with the use of sharped strings on some tracks. The player uses nails.

The guitar is, again, closely miked on this recording and is very present and forward. The playing, while heavily ornamented in period style, also reflects Eisenhardt’s background as a performer of music of the Romantic period. The sound is rich and full. The playing is clean and not fussy. The music sounds heavily influenced by Bach’s magnificent sets of dance suites (most notably for solo violin and cello). The playing emphasizes the harmonic structure and implicit polyphony of the works, rather than foregrounding the melodic line.

Like much of the obscure music for fretted instruments composed before 1800, the music is mostly unremarkable. The character of the dances isn’t well differentiated among the short movements. That’s not to say that the music is unpleasant, particularly given the excellent performances. They are a kind of baroque cocktail music. A couple of the gigues and capriccio pieces are spirited. With its full-throated style, the playing, to a certain degree, documents the evolution of the historical performance of fretted instruments from the time of Eisenhardt’s debut to the present, when players are generally much more restrained, and even precious.

Sospiro: Alessandro Grandi, Complete Arias, 1626, Bud Roach, Tenor and Baroque Guitar, Musica Omnia 2013, 70’34, 23 Tracks

The singer/songwriter tradition goes back substantially beyond Topanga Canyon in the 1960’s, as lutenists well know. But the practice was widespread in Italy as well and had its own superstar in the form of Petrarch (Francesco Petrarco, 1304-1374). Like Leonard Cohen, Petrarch wrote his poetry in a vernacular dialect. In his case, Italian (rather than the more conventional Latin of the time) – but he didn’t write his own music. In the 16th Century, particularly with the movement from polyphony to monody, Petrarch’s poetry became all the rage. Caccini, in particular, is known for his settings of Petrarch’s moody, love-struck verses.

Alessandro Grandi (1568 -1630) set (probably) his own words to music to be accompanied by guitar, and Canadian Bud Roach sings and plays them on this recording. The outstanding notes accompanying the recording credit this as the first recording of Grandi’s secular music. And much is made in the notes of the validity (and superiority) of baroque guitar rather than a continuo group including theorbo, for the accompaniment to these songs. Grandi’s career was principally in Venice and Bergamo, the style of the songs has the Roman character of his contemporary, Caccini – while the influences of the North are clearly apparent. The songs are uniformly charming and lovely. These unknown songs were certainly worth recording.

The verses appear on the page very much like Petrarch’s, in strophic, sonnet form – many in rhyming couplets. The subject of songs is the usual invocations of figures from myths and of the natural world – within the context of the lamentations of the heart sick lover. As in Petrarch, the slings and arrows of aspirational or lost love are the subjects of most of the verses. The songs have, for the most part a chordal accompaniment – with the chords arpeggiated by the guitarist – although there is also both of resqueado and punteado playing as well. The microphones were placed well away from the performer, putting the guitar very much in the background and foregrounding the singer and the words. The playing is for the most part unornamented, while the vocal line is stylishly and tastefully embellished. Roach deploys an instrument modeled after one from Spain of around 1690. The playing is reserved and musical.

Roach’s vocal approach is of the “English Tenor,” variety, lacking operatic richness. But the style is fully appropriate for the material, and the words come first, as they should. Roach really sells these songs, bringing to them the appropriate passion, humor and tristesse. Roach sings with a reedy head-voice, with absolutely accurate pitch and perfectly even, well-supported vocal production. The 22nd track, “Sprezzami, Bionda” is particularly notable for the wit of its internal rhymes, repeated consonants and rhythm, and, like the rest of the recording, sung and played with great spirit and flair.

Sonatas for Baroque Guitar, Richard Savino, Ludovico Roncalli: Capricci Armonici, Dorian 2008, 35 Tracks, 55’47

This recording has been in the Lute Society inbox for quite some time, and the featured performer, is well known here in the United States. He is a professor at both the San Francisco Conservatory and Cal State Sacramento, and his recent performances and recordings with his group, El Mundo, have been notably outstanding (the recent Archivo de Guatemala on Naxos is a standout). The recording includes six of nine suites of short dances composed by Bergamo nobleman and priest Ludovico Roncalli in and around 1692, his Opus 1 and only. Note to Ludo: don’t quit your day job. According to the liner notes, these suites are a standard part of the modern guitarists repertoire, though.

The recording and performance are superlative. The 2004 José Espejo 2004 instrument after Stradivari sounds clear and present. The tuning includes a single bourdon on both of the 4th and 5th courses. Savino is able to produce both a rich sound, while maintaining the fleetness of the ornamentation. The ornaments, while not flashy, are impressively played and tastefully deployed. He makes the most of these conventional, uninspired pieces. They are totally typical of the vernacular (if courtly) music of the period, without any particular melodic, harmonic or rhythmic distinctiveness. Definitely from the second or third drawer. Here, though, the various dance movements are played in such an expressive, varied fashion, with distinctively sophisticated playing, that makes the recording a thoroughly enjoyable musical experience. Ludo would have been thrilled to get such attention paid to his only known composition (if, as a performer, he could get past his jealousy).

Roncalli: Complete Guitar Music, Bernard Hofstötter, Brilliant Classics , 2021, CD 1, 28 tracks, 49’49: CD 2, 26 tracks, 41’56

More recently, all 9 of Roncalli’’ sonatas were recorded (on two CDs) by Austrian lutenist Bernard Hofstötter, playing what the booklet says is an instrument attributed to Venetian maker Matteo Sellas in 1640. Hofstötter has the consummate virtue of having studied law as well as fretted instruments – which is certainly to his great credit. This is Roncalli with brawn: with a big, dramatic closely miked sound. It includes Sonatas 4, 6 and 9, which are not included on Savino’s disk. At times the sound seems to be coming from a modern, metal strung guitar rather than from an authentic 17th Century axe (with only the 4th course including an octave bass). The playing here demonstrates why this music is popular with modern guitarists. It shows off both the performer and the instrument to great advantage. The useful note explains about the harmonic and thematic structure of the suite movements, which gives the listener some valuable guideposts in approaching the sonata/suites.

The playing is fit for a large auditorium – full of romantic variation and ornate (rather than virtuosic or flamboyant) ornamentation. Particularly noteworthy is the frequent bending of pitch leading into a new phrase. There is also a fair amount of playing in the rasgueado style, adding to the variety of the performances. The notes indicate that Roncalli leaves the ornamentation to the discretion of the player. Hofstötter takes that hint to heart and ornaments up a storm. But the playing can ultimately only be described as engaging and beautiful; with warmth and drama – far from the starchy caricature of historically informed performance. Chaste it is not! These two recordings display very different, equally valid approaches to the apparently simple little five course Spanish guitar. There is no room here among fretted instrument players for purists!

Milán/Narváez, Giuseppe Chiaramonte, Brilliant Classics, 2021, 27 Tracks, 63’07

And then there is Renaissance music played on a modern guitar. The music on this recording is from Luys Milán’s Libro de música vihuela de mano intitulado El Maestro (in two volumes) and Luy de Narváez’ Los seys libros del Dephín de música de cifras tañer vihuela, both from the early 16th Century and, as entitled, written for vihuela (and therefore playable on the seven course renaissance lute), but here played by Italian guitarist, Giuseppe Chiaramonte. Another polymath, Chiaramonte has been awarded degrees in both biomedical engineering and electronic engineering.

Milán’s work, 18 short pieces are on this recording, mostly in the form of fantasias. Varváez’ nine pieces are mostly variations, differencias in Spanish. The word that comes to mind in describing the playing, particularly as compared to playing on historical instruments, is “orchestral.” Notable, are the resonant bass notes, that simply aren’t possible to bring out with such presence on the lute or baroque guitar. It is as if this guitar had a sustain pedal. The effect is much like playing baroque music on a modern piano, rather than on a harpsichord. Fast passages are played with enhanced legato. There is a long decay to the sounding of the notes, which influence the manner of playing. One hears the fingers sliding on the metal strings. The modern instrument allows Chiaramonte to employ wide variations of volume and rhythm. This is unornamented music, except that sometime Chiaramonte arpeggiates the chords, and sometimes not – his choices always tasteful. This is aristocratic, highly measured playing. One misses the characteristic distinctiveness of gut strings and smaller bodies but gains in projection and variety.

Different instruments, different approaches, and different styles of playing from a time when virtuoso guitarists were improvisors/composers and court stars – like Taylor Swift – but then again not. Notwithstanding that the number of buyers for these disks are surely limited, there certainly are a lot of them featuring erudite playing.

Andy Manshel studies the lute, theorbo and guitar, and has a particular interest in baroque opera.