Osvaldo Golijov’s work about the murder of the Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca in 1936 tells its haunting story with ferociously contemporary musical style.

By

Heidi Waleson

Oct. 17, 2024 at 5:39 pm ET

Daniela Mack PHOTO: MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA

Operagoers who think that Bizet’s “Carmen” is Spanish should be sure to catch Osvaldo Golijov’s “Ainadamar,” which had its Metropolitan Opera premiere on Tuesday and runs through Nov. 9. Directed by Deborah Colker, this 85-minute phantasmagoria plunges into the death-haunted essence of flamenco, its gritty harshness underpinning even its moments of lyricism. Mr. Golijov, who was born in Argentina, manipulates flamenco’s rhythms, wails and melismas and integrates recorded sounds to create his own ferociously contemporary musical world. The opera had its world premiere in 2003 at Tanglewood; the revised 2005 version is heard here.

Mr. Golijov translated David Henry Hwang’s English libretto into Spanish. His musical language matches the darkness of the story, which concerns the Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca, murdered by fascist Falangists in Granada in 1936 at the start of the Spanish Civil War, as seen through the eyes of actress Margarita Xirgu, who performed Lorca’s works until her death in 1969. The opera, in three “Images,” shuttles back and forth in time. It begins in 1969, as Margarita prepares to go onstage in Lorca’s play “Mariana Pineda,” about a Granada folk heroine who was executed in 1831 for her revolutionary sympathies. The play’s opening ballad—“Ah, what a sad day it was in Granada / The stones began to cry”—sung by a chorus of women at the beginning of each Image, anchors the opera, linking these two political killings a century apart. Margarita recalls her first encounter with Lorca in a time of hope for Spain; vividly imagines his murder; and then, as she is dying, understands that her performances have helped keep his spirit alive.

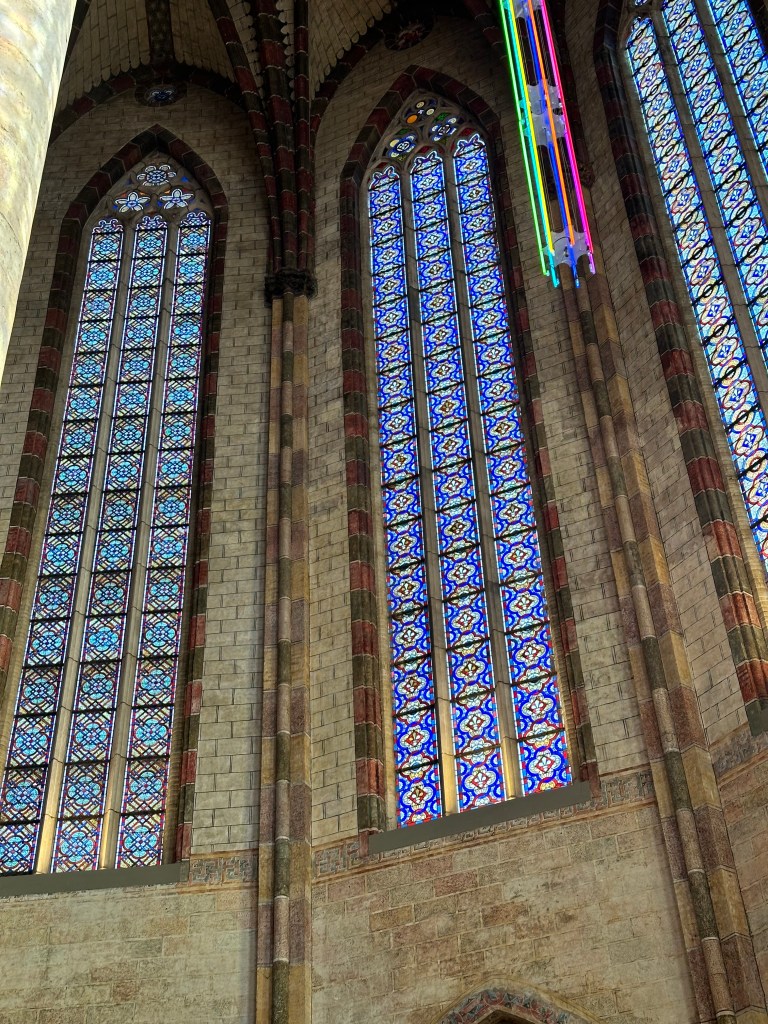

The opera’s dramaturgy is impressionistic rather than narrative, and Ms. Colker, directing her first opera production—she is best known as a choreographer in her native Brazil—leans into that character with a dance-centered production. Jon Bausor’s set features a hanging curtain of strings around a circular playing area; its rippling surface suggests the haziness of memory as well as the water of Ainadamar (Fountain of Tears) where Lorca was killed. Locations are not specified; we are inside Margarita’s haunted memory, with help from Tal Rosner’s soft-edged projections, Mr. Bausor’s period costumes, and Paul Keogan’s dramatic lighting.

A female chorus of 18 “Niñas” (girls), bolstered by several dancers, moves like a corps de ballet around Margarita; as Lorca sings a rhapsodic aria about the statue of Mariana Pineda that inspired him, we see a dreamy vision of four women dancing on pedestals; two solo flamenco dancers, choreographed by Antonio Najarro, offer striking images at crucial moments, as if to embody the intensity of Lorca’s verse with their exaggerated postures. For Lorca’s confession before his murder, the staging subtly suggests Christ’s Passion, a thematic thread in the opera.

Though arresting and viscerally expressive of Mr. Golijov’s score, the production does less well by the principal characters, who are underdirected and sometimes lost in the overall imagery. Angel Blue’s plush soprano seemed out of place for the ululating wildness of Margarita’s vocal anguish; she was most comfortable in the purely lyrical, almost Puccini-esque moments. Mezzo Daniela Mack was eloquent as Lorca, handsome in an all-white suit and plaintive before the execution. Elena Villalón brought a pure, fearless soprano to the role of Nuria, Margarita’s student and interlocuter. The most electrifying vocal contributions came from Alfredo Tejada as Ramón Ruiz Alonso, the Falangist who pursues and arrests Lorca, singing the howling flamenco cante jondo. The vocally protean Niñas were affecting in styles from edgy harshness to ethereal water music—Jasmine Muhammad and Gina Perregrino were standout soloists as the Voices of the Fountain.

Led by Miguel Harth-Bedoya, the orchestra is a potent force in “Ainadamar,” encompassing jagged flamenco rhythms with guitars, serene strings, and trumpet calls; there is a host of expressive percussion, from eerie vibraphones for the fountain music to folk drums and castanets. The principal singers and some of the instruments were amplified, and at times Mark Grey’s sound design favored the orchestra at the expense of the singers. Mr. Golijov ingeniously builds pre-recorded sound effects—including hoofbeats, water, the voices of praying children and gunshots—into the score; in one especially chilling series of interpolations, recordings of Falangist radio broadcasts blare out, each ending with the words “Viva la Muerte!” (Long live death!). Violence, death and apotheosis are certainly operatic staples, but “Ainadamar,” using atypical musical and theatrical modes to depict a real event that is not far in the past, powerfully excavates those conventional themes for a very different kind of impact.

Ms. Waleson writes on opera for the Journal and is the author of “Mad Scenes and Exit Arias: The Death of the New York City Opera and the Future of Opera in America” (Metropolitan).